A central use of reserves held at Federal Reserve Banks (FRBs) is for the settlement of interbank obligations. These obligations are substantial—the average daily total reserves used on two main settlement systems, Fedwire Funds and Fedwire Securities, exceeds $6.5 trillion. The total amount of reserves needed to efficiently settle these obligations is an active area of debate, especially as the Federal Reserve’s current quantitative tightening (QT) policy seeks to drain reserves from the financial system. To better understand the use of reserves, in this post we examine the intraday flows of reserves over Fedwire Funds and Fedwire Securities and show that the mechanics of each settlement system result in starkly different intraday demands on reserves and differing sensitivities of those intraday demands to the total amount of reserves in the financial system.

Background

As part of the normal course of business, banks settle obligations amongst themselves by drawing upon reserves they hold at the FRBs. For cash-only obligations, banks most often use the Fedwire® Funds Service, a large-value real-time payments system. The total daily value of transfers made over Fedwire Funds is substantial, with the average daily value sent in the second quarter of 2024 equal to $4.5 trillion.

Another settlement system operated by the FRBs that uses reserves is the Fedwire® Securities Service, a real-time delivery-versus-payment system. This system is linked to the FRBs’ book-entry ledger, on which the U.S. Treasury, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and other agencies issue securities. Among other services, Fedwire Securities enables the simultaneous movement of securities against reserves across accounts. There is also a substantial daily movement of reserves over Fedwire Securities, with the average daily value of reserves delivered in the second quarter of 2024 equal to $2.1 trillion.

For both settlement services, banks usually initiate transactions on behalf of their customers. Those customers, or the underlying nature of the transaction, can dictate that the transactions be completed by certain deadlines within the day. The intraday flow of reserves in and out of a bank’s account, however, can be quite large relative to a bank’s balance. A previous Liberty Street Economics post showed that in 2015, a year of abundant total reserves, the largest ten banks still faced outflows over Fedwire Funds (alone) that were larger than their beginning-of-period balance at the FRBs. Banks then, often need to strategically manage the timing of transactions over both settlement systems, balancing the demands of their customers for earlier settlement within the day against the bank’s balance of reserves at the FRBs (and the bank’s appetite to access intraday credit from the FRBs).

What Is Each System’s Intraday Liquidity Demands?

Fedwire Funds is designed to accommodate only credit payments, so the account holder sending reserves initiates the transfer. Accordingly, when an account holder’s balance is running low, that bank often strategically delays sending payments over Fedwire Funds until later that same day, with the expectation that incoming payments will replenish that bank’s balance (see “Intraday Liquidity Management: A Tale of Games Banks Play” and “How Abundant Are Reserves? Evidence from the Wholesale Payment System”). Hence, when a bank is facing a constraint on the reserves it is holding within the day, the bank is likely to respond by delaying payments made over Fedwire Funds until later in the day.

Fedwire Securities is designed so that the account holder sending securities (and receiving reserves) initiates the transaction. Given that account holders value holding reserves for intraday liquidity needs, even on the margin, the account holders that face obligations to deliver securities for a given day will often deliver those securities as early as possible.

These intraday demands on reserves drive the distribution of transactions within the day across each settlement service. The chart below shows the percent of total transactions by value that occur within 1.5-hour buckets over the Fedwire Funds operational day (9 pm of the day before to 7 pm of the current day, eastern time) for the second quarter for 2024. There is an uptick in payments made with the opening of business on the U.S. East Coast, but the busiest interval is from 3-4:30 pm. This late-day bunching of payments is consistent with banks managing intraday liquidity demands, an observation made in “Changes in the Timing Distribution of Fedwire Funds Transfers.”

Banks Settle More than Half of Fedwire Funds Transactions in the Last Third of the Day

Percent of daily total transactions

Notes: The chart shows the percent of all daily transactions occurring in each 1.5-hour bucket over the Fedwire Funds operational day (9:00 p.m. of previous calendar day to 7:00 p.m. of the current day, Eastern Time). The sample is the second quarter of 2024.

Turning to Fedwire Securities, the following chart shows the percent of total transactions by value that occur over this settlement system’s operational day (8:30 am to 3:15 pm, Eastern Time) in the second quarter of 2024. The main takeaway is that more than 60 percent of total transactions by value occur right at the opening of Fedwire Securities. As with Fedwire Funds, this behavior is consistent with banks valuing reserves for intraday liquidity. Furthermore, the concentration of settlement at the opening creates substantial demands on reserves—in the first 30 minutes after opening, about $1.05 trillion of reserves, on average, are transferred over Fedwire Securities.

Most Fedwire Securities Payments Occur in the First 30 minutes after Opening

Percent of total daily transactions

Notes: The chart shows the percent of all daily transactions occurring in each half-hour bucket over the Fedwire Securities operational day (8:30 a.m. to 3:15 p.m. each day, Eastern Time). The sample is the second quarter of 2024.

How Does the Intraday Timing of Payments Change with the Level of Aggregate Reserves?

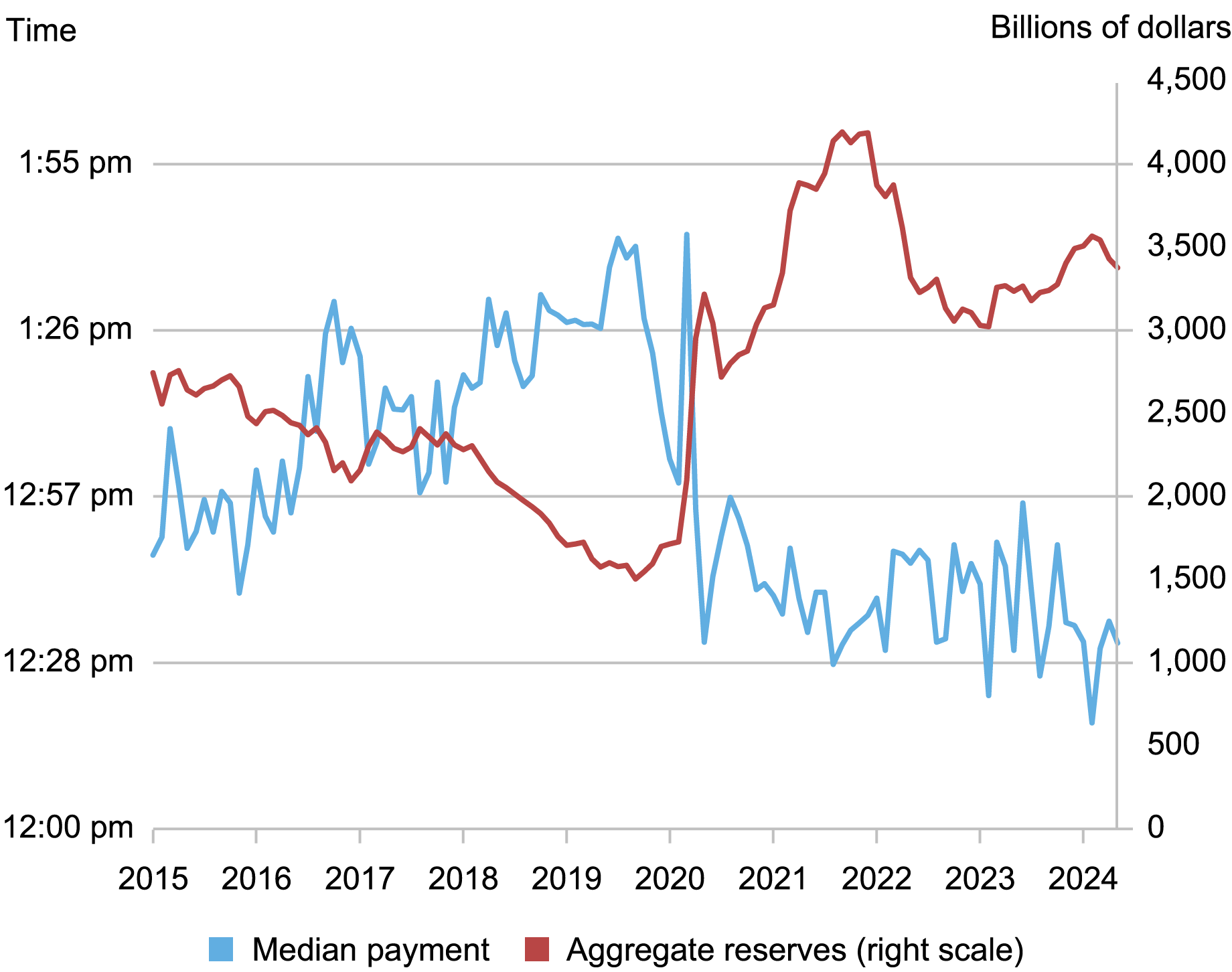

When the Federal Reserve changes the total amount of reserves held by banks, it directly affects the intraday demand for reserves by banks. In particular, when the Fed increases the total amount of reserves, banks’ concern over the intraday flows of reserves diminishes, as discussed previously. This dynamic is seen in the chart below that plots aggregate reserves alongside the time of day when half of the total value of Fedwire Funds payments have been sent (time of median payment). When there are low levels of aggregate reserves, banks delay payments by a substantial amount. Indeed, from 2015 to 2019, the steady decline in aggregate reserves from more than $2 trillion to less than $2 trillion is accompanied by an almost one-hour shift later in the time of the median payment. Furthermore, the substantial increase in aggregate reserves from 2019 to 2022 coincides with a large shift in payments being settled earlier in the day.

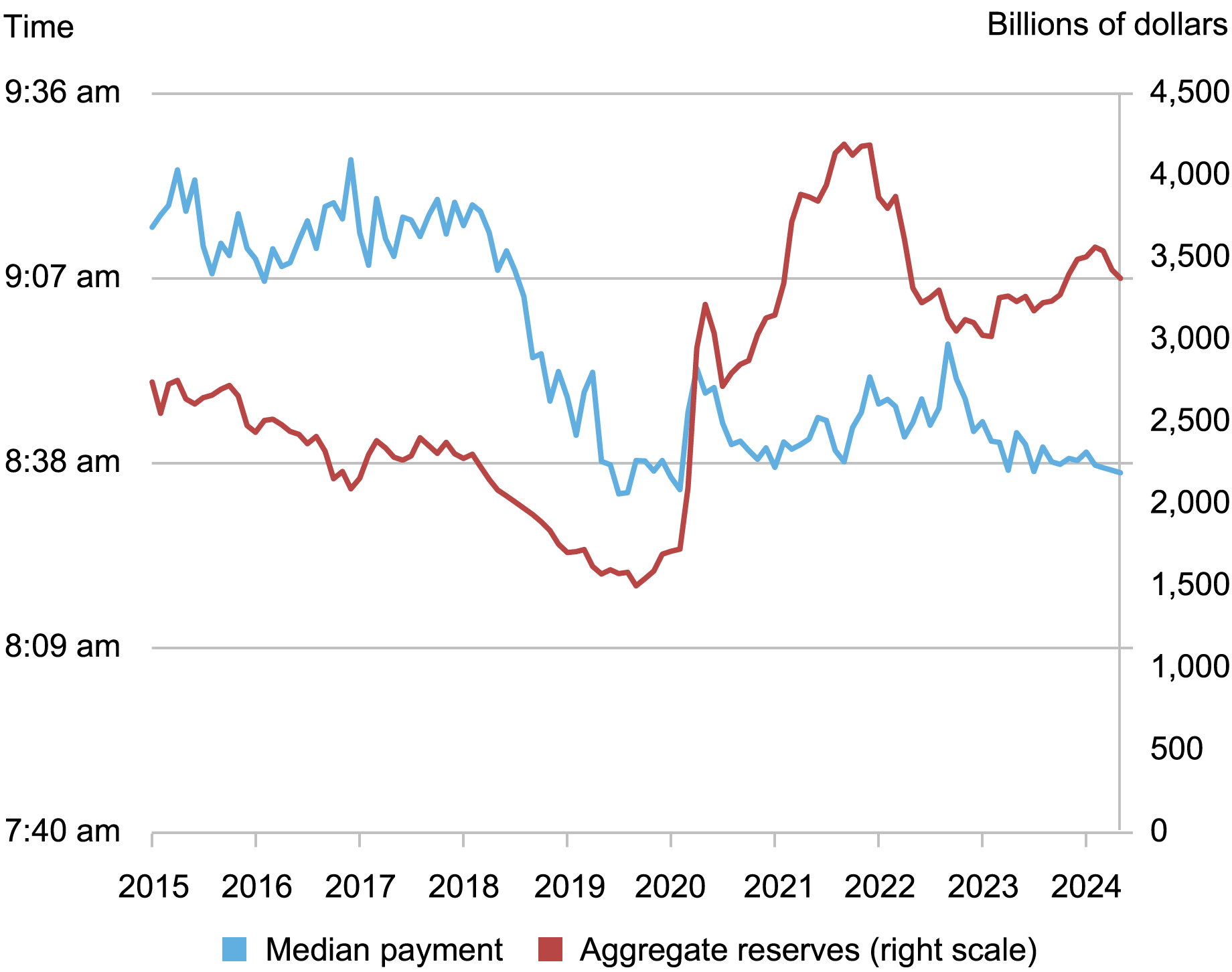

This association between intraday settlement timing and aggregate reserves is not seen with Fedwire Securities. Rather, the timing of these transactions remains bunched at opening from 2015 to now. Starting in the first half of 2018 and ending in the first half of 2019, there is a 30 minute earlier-in-the-day shift in the time of median payment, but this shift is due to changes in the custodial business and is unrelated to the level of total reserves.

The Timing of Fedwire Funds Payments Reacts to the Total Level of Reserves …

… Whereas the Timing of Fedwire Securities Payments Does Not.

Notes: The top chart shows when in the day the first 50 percent of total transfers has occurred over Fedwire Funds (navy line). The bottom chart shows when in the day the first 50 percent of total transfers (as measured by the cash amount) has occurred over Fedwire Securities (navy line). In both figures, the maroon line reflects the total amount of reserves held by banks. Both figures span January 2015 to May 2024.

Takeaway

The timing of payments over Fedwire Funds has garnered attention because shifts in the timing of payments are informative about banks’ demand for reserves and, consequently, the overall level of total reserves in the system. Banks also need substantial amounts of reserves to settle their obligations on Fedwire Securities, especially right at opening. Unlike what is seen in Fedwire Funds however, the intraday timing of settlements on Fedwire Securities is invariant to changes in the total amount of reserves in the system.

Adam Copeland is a financial research advisor in Money and Payments Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Sarah Yu Wang is a research analyst in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Adam Copeland and Sarah Yu Wang, “The Dueling Intraday Demands on Reserves,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 21, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/10/the-dueling-intraday-demands-on-reserves/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

Source link