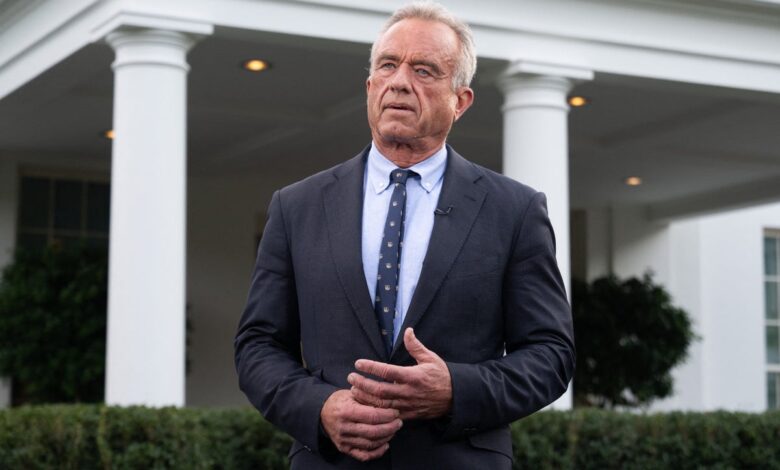

On Wednesday Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., and the U.S. Department of Agriculture released new official guidance that effectively overturns the food pyramid. The recommendations encourage Americans to eat “real food” and to consume more saturated-fat-rich foods such as red meat and whole-fat dairy.

The dietary guidelines inform U.S. nutrition policy, shaping dozens of federal feeding programs, including meals for the military and school lunches. In a statement, the American Academy of Pediatrics hailed the guidance as focused on whole foods for kids. “We commend the [guidelines’] inclusion of the Academy’s evidence-based policy related to breastfeeding, introduction of solid foods, caffeine avoidance and limits on added sugars,” said AAP president Andrew Racine.

Yet the new guidelines’ inclusion of red meat and animal fats contradict decades’ worth of past recommendations and scientific evidence that had directed people to eat less saturated fats and more unsaturated fats, such as those found in olive oil. In one section, however, the guidance recommends that no more than 10 percent of a person’s calories should come from saturated fats and states that “significantly limiting highly processed foods will help meet this goal.” In response to Scientific American, an HHS spokesperson said that the 10 percent cap on saturated fats remained unchanged from previous guidance. That said, in supplemental material reporting the review of evidence, the new guidelines’ advisory committee generally voted to partially or fully omit most previous recommendations that had encouraged replacing saturated fat, including butter, with unsaturated fat, particularly from plant-based sources.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The changes reflects Kennedy’s avowed aversion to ultraprocessed foods, which play an increasingly large part in the average American’s diet. He has focused much of his ire on seed oils in particular, arguing that they should be swapped out for animal fats. But experts say that seed oils are generally safe when they are used properly and that encouraging Americans to eat more saturated, animal-derived fats likely poses a graver risk to heart health.

“I know of no evidence to indicate that there would be an advantage to increasing the saturated fat content of the diet,” says Alice Lichtenstein, senior scientist at the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University. “People shouldn’t be scared of fat, but they should keep in mind that it’s better to get it from plants than animals,” she says. “That’s what the bulk of the current evidence suggests.”

The HHS spokesperson told Scientific American that nutrition scientists and subject-matter experts who were selected for the guidelines’ advisory committee conducted comprehensive scientific reviews and that “evidence was evaluated based solely on scientific rigor, study design, consistency of findings, and biological plausibility. All reviews underwent internal quality checks to ensure accuracy, coherence, and methodological consistency.”

Humans need fat for basic cellular and biological functions in the body—fats, or lipids, are essential for creating cellular membranes, absorbing hormones and vitamins and regulating body temperature. The fat we eat generally falls into the two main categories of saturated and unsaturated. The primary difference is their arrangement of fatty acids—chains of hydrogen and carbon molecules.

In saturated fats, which are commonly found in meat, cheese and butter, the carbon molecules in the chain are linked with single carbon bonds and contain so many hydrogen atoms that the chain lies flat. This structure allows chains to align and pack tightly together, which is why saturated fats—such as those in butter and tallow (rendered animal fat)—generally stay solid at room temperature.

Unsaturated fatty acid chains, on the other hand, have double carbon bonds that cause them to curl and kink, so these fats mostly stay liquid at room temperature. These include monounsaturated fats (such as those in avocado and olive oils), polyunsaturated fats (such as sunflower oil) and trans fats (such as chemically processed vegetable oils that are often used in processed foods).

The arrangement and length of fatty acid chains also influence how our body processes fats. Unsaturated fatty acid chains tend to be incorporated into various parts of cells, such as cell membranes, to help them function properly. Saturated fatty acid chains generally get stored in fat tissue.

“Biology is not black or white, but the type of fatty acid pretty much tells you where it’s going to go and how your body is going to use it,” Belury says.

Most foods naturally contain both saturated and unsaturated fats. It’s the overall amount consumed that matters for health, Lichtenstein says. In general, animal fats, including meat and dairy fat, have a higher proportion of saturated fatty acids.

Numerous studies and randomized clinical trials that compared diets high in saturated fat with those high in unsaturated fat have shown that the former increase levels of low-density lipoproteins (LDL), a type of cholesterol that, at high levels, can lead to strokes or heart attacks. More recent research also suggests that saturated fats are linked to an increased risk of insulin resistance, a precursor to type 2 diabetes and obesity-associated heart disease, Belury says.

Lichtenstein adds that the new guidelines seem to confuse “healthy fats” and essential fatty acids. “Those recommended as ‘healthy fats,’ butter and beef tallow, are low in essential fatty acids,” she says. “Even olive oil, which is certainly a good oil to use, is not particularly high in essential fatty acids relative to other plant oils.”

Leading medical societies offer their own guidance on dietary fat intake. The American Heart Association recommends that less than 6 percent of total calories should come from saturated fat. In a 2,000-calorie diet, that’s about 13 grams or less of saturated fat per day—roughly equivalent to two tablespoons of salted butter or a single quarter-pound fast-food cheeseburger.

Experts have historically reevaluated and changed nutrition recommendations based on new, high-quality evidence. For example, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration previously tweaked guidance around trans fats after research found that these fats increase LDL cholesterol at a comparable level to saturated fats while simultaneously reducing “good” cholesterol. Recommendations are not made without a comprehensive review of the literature, Lichtenstein says. “It’s the cumulating evidence that is what’s really important,” she adds.

Editor’s Note (1/7/26): This article was updated after posting to include additional information and expert insight. This is a breaking news story and may be updated further.

Source link