“I just completely screwed that one up and didn’t mean to. Honestly, it was like losing the playoffs.”

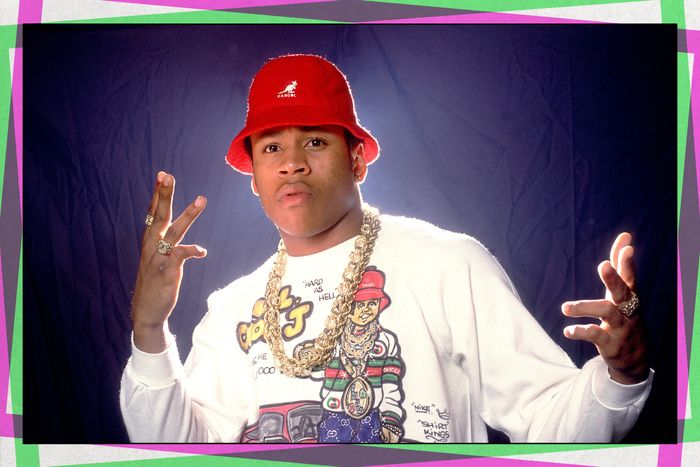

Photo: Vulture; Photo: Paul Natkin/WireImage

Forty years into being America’s Poet Laureate of Braggadocio, LL Cool J’s legacy remains unparalleled. As a teenage firebrand claiming to outwrite Edgar Allan Poe and offering to make Madonna scream, he released his tectonically hard debut Radio in 1985 — the first release on Def Jam records — before becoming a full-fledged superstar with 1990’s Mama Said Knock You Out. Though countless rappers have since vied for his title as the “Greatest of All Time,” nothing could stop the always-magnetic LL from delivering, whether R&B crossover (1995’s “Hey Lover”), hardcore battle rhymes (1997’s “4, 3, 2, 1”), Southern-fried bounce (2004’s “Headsprung”), or vintage rap-rock (2013’s “Whaddup”). Somewhere in between, he found time to become a seasoned film actor, a five-time Grammy host, and a television icon across 14 seasons of NCIS: Los Angeles.

Still on Def Jam, LL Cool J is now making us face an unlikely but totally believable reality: One of 2024’s best rap records is by someone who was stealing scenes in Krush Groove before Kendrick Lamar and Drake were alive. Due this Friday, LL’s The FORCE — masterfully produced by Q-Tip at a midpoint between contemporary NYC minimalism and the frayed edges of vintage Dilla — features the once and future Ripper in full blackout mode, off limits to challengers and putting suckers in fear. In essence, R.I.P. meatballs.

In a lengthy Zoom call, he broke down the biggest, deffest, and most misunderstood parts of his storied career. However, the undisputed king of scorched-earth wax battles couldn’t pick one of his many lyrical TKOs. “They don’t really occupy a lot of space in my head,” he says. “The one thing about me with the rap shit is that I’m an MC first, and I don’t take it personally.”

I would say “Doin’ It.” I think the beat, the lyric, the flow, the collaboration, the moment, the visual — it’s perfect. It was a different time, so the explicit version isn’t even really explicit in this day and age. But at that time it was risqué. I mean, it’s sexy, but it’s pretty mild compared to what’s going on now. You know, they talking about brown booty holes now.

It would have to be “Don’t call it a comeback.” It’s not just about hip-hop and LL. It transcends all that. People go through things and switch their lives up and use “Don’t call it a comeback.” It just says so much. Tiger Woods had that moment — he came back and said, “Don’t call it a comeback.”

At the time, people had essentially written me off. Me wearing the diamond chains and the fancy cars and the fur coats and having the girls on the cover — all the things that would become synonymous with hip-hop, I was introducing those elements to the game, and I was paying for it. That was a song that was written out of frustration. I was clawing my way back. I was snatching victory out of the jaws of defeat. It was like a buzzer beater, you know? I remember I was in a room full of guys and they had the Olde English out and the SP-1200, and the beat was playing. It came to me. A lot of my lyrics just come to me. When you get out of the way, they just pop in your head.

I mean, I damn near don’t even want to bring it up, but if I have to it would be “Accidental Racist.” Yo, I completely blew that one. Like, in terms of my intention versus how it came off to people. Oh my God. Like, I missed the mark crazy. And it always bothered me because my intention was absolutely not how it came off. I feel like it was like having a hot date with a vegan and setting everything up wonderful and the first thing the chef brings out is a big, juicy steak. But you think it’s vegan still, you know what I mean? I completely screwed that one up and didn’t mean to. It was the worst kind of miss because it’s one thing to fail; it’s another thing to fail when you’re looking to do the right thing and you’re looking to say the right thing.

And then it goes Gold, which is really fucking bizarre. I don’t even have a copy of the plaque. I never even asked for one. Like, I made songs that just weren’t great songs. Okay. I can live with that. But to have a song that garners that much attention and actually negatively impacts the way people perceive my intention was the worst. That shit was the worst. I think it was just the idea that, somehow, I was looking to appease racists. Yo, bro, that is not what I meant. To put it in simple terms, I was trying to say, “First of all, just leave me the fuck alone because of what I look like. Let’s start there. And then we could see what else can happen from there.” But instead, I said the iron chains and the durag … It just was a bad metaphor. It was just all wrong.

“Going Back to Cali” aged really well. It’s a very cool video, bro. The bikini small, heels tall, the ocean, the fish bowl. I learned how to drive a stick on that video. I felt like I was in a foreign country, man. I felt like I was on another planet. I was fresh out of Queens and I’m running around on Venice Beach. That may not seem like a big deal now, but when you in the hood your whole life, and you go out to Venice and you driving Corvettes, this porn star’s rubbing my chest … It was wild.

That was a time when MTV didn’t really play many rap videos. I thought Martha Quinn was cool. We were like, “Yo, let’s get her in the video to give it some energy and to make it a little bit cooler and maybe they’ll take a look at this song.” I had the “I’m Bad” video. That one was really good too, but it didn’t get the same play. At that time, being a young Black rap artist — and I’m not saying this in any bitter way, but I gotta call it what it is — I wasn’t getting the same treatment as the Beastie Boys. I wasn’t getting those same looks, so it was a little bit tougher for me. Like, can you imagine if Ad-Rock and them made “I’m Bad,” and they were spinning around like that and doing all that shit, what that would’ve been?

Canibus. Him and Moe Dee both came at me really hard. A lot of them guys were more interested in coming after me than I was interested in going after them, to be honest. Canibus came at me the hardest. He just couldn’t tackle me. Moe Dee did as well with “Death Blow.” You know, with the “L lower lack, living in limbo, laborious …” [Laughs.] I remember being a little kid listening to this shit, like, The fuck is he talking about? Just turn that shit off. And then Canibus getting Mike Tyson on “Second Round K.O.” was strong. That was slick. Me and Mike were cool. But they gassed Mike up and he didn’t even know what he was doing, you know what I’m saying? He didn’t know what song he was getting on. At least that’s what I’d like to think. It was just Team USA in South Sudan, that’s all. [Laughs.] I still got the point. I still walked away with the trophy.

Bringing Canibus onstage at Barclays. I got a sold-out show with Run-D.M.C., and I bring him onstage to do “4, 3, 2, 1.” For me, that was big. I just reached out and was like, “Yo, I’d love for you to be a part of it. Come out.” And, you know, he agreed to do it, and we took a picture and everything, and I thought we was good. Another time was when I shouted him and Moe Dee out at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. But then I seen the guy making comments and he was unhappy with me shouting him out. I thought it was patched up. But I guess people take things the way they take things — I don’t know. For me it was just my way of trying to show respect to competitors and just give love and keep it moving.

The one thing about me with all of those battles is it was never a personal thing. It was more like Steph and LeBron playing against each other. It wasn’t me not liking them personally and hating them or having any real ill will toward them. It was just like, we did what we did, we said what we said, cool. We could shake hands after the game. It wasn’t that deep. But, you know, for some of these guys, I guess they lay awake at night staring at the ceiling sharpening they toothbrush and shit. [Laughs.]

It’s on a little indie album I did. It’s the only album I did that wasn’t on Def Jam. “Not Leaving You Tonight.” Yo, that song right there is amazing, with Fitz and the Tantrums and with Eddie Van Halen playing that guitar solo. That should have been bigger. It should have played on every station in the country. That is the only song out of all of the songs in my career that I look at and say, That song is supposed to be Diamond.

I had my toe kind of halfway in the water as a musician ’cause I was doing a TV show. And I just was in a bubble. I made that experimental album and I didn’t focus. So I’m not blaming anyone. I can’t really point the finger. This is kind of a little corny and presumptuous, but it should have went on its own. It’s just that good to me. “These lines on my face are a sign of the times.” Like, come on, bro — talking about growing older and maturing, and the sound of that. I remember playing that song for Rick Rubin and he was like, “Wow, that’s really special.” That’s a song that I’m really, really proud of even though it didn’t have the commercial firepower that some of my other songs had. One day, somebody will be smart enough to remake that song and it will go through the roof.

Clockwise from left: At the Grammys, with Rick Rubin, In Too Deep with Omar Epps. David Crotty/Patrick McMullan via Getty Image; Photo: Jeff Kravtiz/FilmMagic, Inc.; Photo: Getty Images.

Clockwise from left: At the Grammys, with Rick Rubin, In Too Deep with Omar Epps. David Crotty/Patrick McMullan via Getty Image; Photo: Jeff Kravtiz/…

Clockwise from left: At the Grammys, with Rick Rubin, In Too Deep with Omar Epps. David Crotty/Patrick McMullan via Getty Image; Photo: Jeff Kravtiz/FilmMagic, Inc.; Photo: Getty Images.

In Too Deep. Playing the villain. Just being able to let loose and put guns in people’s mouths and put ’em on pool tables and torture ’em and all that. Like, that was right up my alley. I loved everything about it, man. It was loose, it was street, it was ghetto. It was enjoyable playing a completely different person. And working with Robin Williams on Toys was super-fun. Matter of fact, I’ll give you three: Halloween H20. Jamie Lee Curtis was great. She was so fun to work with.

Probably Rollerball. At the end of the day it’s like, The fuck was I doing on that motorcycle in that racetrack, man? Like, Where are you going, bro? What are you doing? Why are you and Chris Klein in a fucking van? That shit was ridiculous, man. But you know, I didn’t know no better. I look back on it like, “Not your best work. Todd.” [Laughs.] I watched that shit at the premiere and walked outta that motherfucker like, “Welp, that happened.” Me and Chris Klein should apologize to each other for that bullshit. [Laughs.]

Throat goat. That’s real wild. [Laughs.] Yo, G.O.A.T., that went everywhere, B. The fact that it made it all the way there, that’s kind of bananas.

“Murdergram Deux,” for sure. Q-Tip played the beat. I actually watched him create a lot of it. It was absolutely amazing to me. Because of the choppiness in the tempo, I felt like Eminem would be perfect for it. We ended up going to L.A. to Dr. Dre’s studio. We recorded together. I would go in and write my verse and record mine in the booth. He would go in and write his verse, record in the booth. We would never watch each other record, except for the very ending when we kind of went back and forth a little.

It just came out crazy to me. I think it’s the perfect example of what I was saying when I made that comment. And I remember how many people were like, “Oh, we don’t need this.” But that’s Twitter. That’s the nature of the beast. It is what it is. But I think that it definitely delivers. I think that song is that moment when you see there is a difference between people really into the craft of MCing and people who are rapping because they can. Like when, in the original “Murdergram” in 1990, I said, “the big showdown, the display of skill,” right? I think this took that idea of the display of skill to another level. The way Em is tripling up at the end and the way we go back and forth, and … it just feels right to me. We sound like a rap group.

I’ve never had a hard song to write. Yeah. [Laughs.] I never had one of those.

It was technically Tiger’s friend who texted the LL lyric during the golfer’s 2011 run, but the point stands.

A former MTV VJ.

Authentic, released in 2013, was the only rap record on 429 Records, a label that also put out post-majors albums by Robbie Robertson, Los Lobos, Joan Armatrading, Camper Van Beethoven and Meat Loaf.