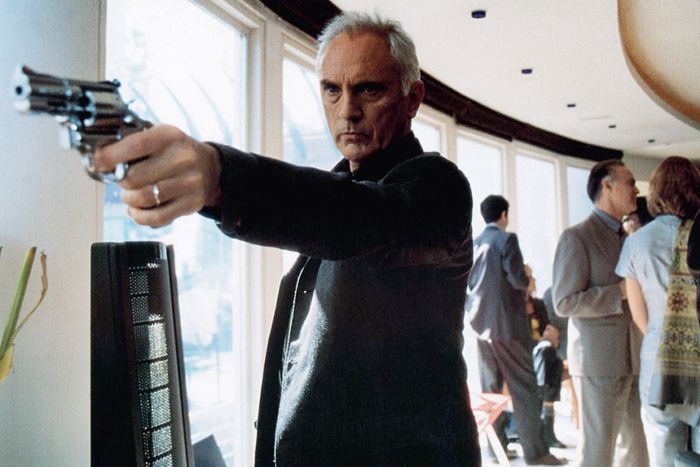

Photo: Artisan Entertainment/Everett Collection

Steven Soderbergh loves a close-up, and he met his ideal subject in Terence Stamp, who died Sunday at 87. “You wouldn’t think a close-up of somebody thinking would have the power that it does because, in theory, it’s static,” Soderbergh told me in a 2023 interview. “But yes, one of my favorite things to do is to have a camera close to somebody’s face as a penny is dropping.” He said that when he’s visualizing a movie while reading the script, “I don’t see locations, I don’t see masses of elements being coordinated, I see … a face with a certain kind of expression on it.”

The apotheosis of Soderbergh’s fascination with close-ups is his 1999 crime thriller The Limey, about Wilson, an English ex-convict who comes to Los Angeles to find out what happened to his missing daughter and, upon finding out that she was murdered, embarks on a revenge mission. The movie is built around close-ups of Wilson (played by Stamp) thinking. He could communicate emotions and information in silent close-ups that other actors would have needed pages of dialogue to express.

As it happens, Soderbergh had originally planned to shoot writer Lem Dobbs’s script in a more traditional way but realized during editing that it didn’t have the every energy and impact he wanted. So he and his editor, Sarah Flack, took the entire thing apart and reassembled it nonlinearly, using the many silent close-ups he’d collected of Stamp and other actors to hold everything together. Soderbergh and Flack had taken close-ups of Stamp around Los Angeles and arranged them nonchronologically to mimic the wanderings of a mind caught between past and present.

The close-ups had to suggest intent yet be sufficiently uninflected to allow the filmmakers (and eventually viewers) to project their own meanings onto them. Fortunately for Soderbergh, Stamp — along with the main cast, which also included Peter Fonda, Lesley Ann Warren, and Barry Newman — were skilled at giving editors a variety of close-ups that communicated basic human conditions but were otherwise open enough to be matched with lots of other shots. The Limey edit was a high-end version of the Kuleshov effect, wherein an identical shot of an actor’s blank face is stitched together with shots of a bowl of soup, a woman on a sofa, and a woman in a coffin. Viewers who watched the three sequences concluded “the man is hungry,” “the man is amorous,” or “the man is sad.” Stamp was whoever you needed him to be.

In The Limey, Soderbergh included flashbacks to Wilson’s early years, taken directly from a previous Stamp role in Ken Loach’s Poor Cow, another tour de force performance where a film’s meanings are carried by his deep eyes, unguarded expressions, and angular face. With decades between the performances, you can see how Stamp was always an astonishingly natural actor who was able to connect directly with the audience using the lens as an intermediary, erring on the side of minimalism and emotional simplicity. He learned a lot from his first film shoot, the 1962 adaptation of Billy Budd, the only feature directed by English actor Peter Ustinov, who was equally accomplished on the stage and in films. Ustinov knew that, unlike in theater, movie actors are being assisted by an entire film crew, including an editor they may never meet. Thus, every choice they make has a force multiplier and it’s not necessary to put across every possible shading all by themselves.

Stamp said he absorbed this philosophy from generational contemporaries like his friend Michael Caine, who once told students in a videotaped acting class that they should strive for a blend of concentration and relaxation. When one of the students asked how it was possible to reconcile those two states, Caine told him to remember that on a film set, “You have no enemies. Everyone is on your side. The camera is like a belt or a net behind you. Someone is standing behind you saying, ‘It’s okay to relax; you don’t have to push it,’ like in the theater.” Stamp seemed to have an instinctive understanding of this approach.

Through the rest of the ’60s, Stamp matured and worked with different kinds of directors. He was in John Schlesinger’s Far from the Madding Crowd (as an unkind sergeant), Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema (as a mysterious man who shows up at the gates of an unhappy Italian family’s villa), and Federico Fellini’s Toby Dammit (as an actor who flirts with the devil). Stamp told The Hollywood Interview that he was a different actor after working with Fellini, who guided him to what he believed was his best movie performance yet.

“By the end of that experience,” he said, “I was no longer acting; I was just being, which prepared me for the experience with Pasolini, who didn’t want acting. Pasolini used to film me without me knowing with his own camera — when I wasn’t on set, when I wasn’t acting. It didn’t take me long to realize what he was doing. He just wanted me being, just being myself, being present in the present. That was a new strata of performance for me.”

After the late 1960s, Stamp’s career cooled because, he later said, the industry was starting to focus on much younger actors and chase the counterculture audience that made Easy Rider a massive hit. Stamp spent several years in India studying spirituality and learning meditation and yoga. He was enticed back to the cinema in late 1976 by director Richard Donner, who offered him the role of General Zod in the first two Superman films, which were to be shot back-to-back over 18 months. Stamp was reluctant to accept the part, less because of the time commitment or the then-disreputable nature of comic-book source material and more because it was a supporting role. He was still wounded by the idea that he was no longer considered leading-man material. Stamp told The Hollywood Reporter that on the Superman sets, the crew “did everything they could to make me look hideous” because he was playing the bad guy. “You know, they lit me from below, they put green makeup on me, they gave me these ridiculous costumes.” And yet, he said, “the camera was still my girl. The camera could always find the best of Terence, and all Terence had to do was give the best of himself.”

His performance as the maniac who wants to kill Superman is another finely honed piece of work, as pure and uncomplicated as his work for Schlesinger and Loach. Zod’s rages sound like an angry man threatening someone from the other side of a parking lot, not the cliched snarling of too many comic-book movie villains. You can almost hear gears whirring as he catalogues each tidbit in the “kill Superman” filing cabinet of his mind. Even his vanity, entitlement, and boredom are human-scaled. His performance is matched in delicacy only by Christopher Reeve’s.

The binding elements of the performances in the second half of Stamp’s career are a seeming lack of ego or want and a corresponding stillness that invites the audience to look at him deeply and study him as we might our own reflection in a mirror. In interviews and public appearances throughout his life, Stamp spoke of the camera with deep affection, as if it were a childhood friend or a woman he’d just fallen in love with.

Zod ended up launching Stamp into the character-actor period of his career, which was more remunerative and often more fun than his leading-man era. He was Sir Larry Wilder, the British financier in Wall Street who rescues a company from the clutches of corporate raider Gordon Gekko (Michael Douglas). He played the devil (again) in Neil Jordan’s horror film The Company of Wolves; the quietly merciless critic who punctures an artist’s self-importance in Tim Burton’s Big Eyes; goodhearted and doomed ranch owner John Tunstall in Young Guns, serving as an unofficial father to Billy the Kid and his gang; and a legendary drag performer named Bernadette Bassenger in The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert.

The last role, Stamp said, was one he had to be talked into accepting. A lot of Bernadette’s journey was about accepting the nonnegotiable facts of aging, something he himself was still rebelling against. He finally said yes after his agent advised him to do it not for career advancement, but for “personal growth.” The film’s director, Stephan Elliott, told the Guardian that Stamp “was absolutely terrified to play Bernadette — he was being voted one of the best-looking men on earth and suddenly in Priscilla he was, and this is a direct quote, ‘dressed up as an old dog.’ But he put the pain of what he was going through into the performance, and that’s what made the film … Terence kept to himself. He was an enigma. And then he’d show up, use the eyes, and turn everybody to jelly.”

Source link