A key question in economic policy is how labor market tightness affects wage inflation and ultimately prices. In this post, we highlight the importance of two measures of tightness in determining wage growth: the quits rate, and vacancies per searcher (V/S)—where searchers include both employed and non-employed job seekers. Amongst a broad set of indicators, we find that these two measures are independently the most strongly correlated with wage inflation. We construct a new index, called the Heise-Pearce-Weber (HPW) Tightness Index, which is a composite of quits and vacancies per searcher, and show that it performs best of all in explaining U.S. wage growth, including over the COVID pandemic and recovery.

The Importance of On-the-Job Search for Labor Market Tightness

Labor market slack is often measured using the unemployment rate or the vacancy-to-unemployment ratio. In a recent Staff Report (Heise, Pearce, and Weber, 2024), we build on the theoretical foundation by Bloesch, Lee and Weber (2024) who argue that wage inflation should instead be strongly related to quits and to vacancies per job seeker. The key argument is that on-the-job search is important for understanding labor market tightness: since most new hires come from other jobs rather than from unemployment, an appropriate measure of labor market tightness must include employed job seekers. Consequently, labor market tightness should be measured by vacancies per searcher, where searchers combine employed, unemployed, and non-employed job seekers, rather than just vacancies over unemployment, or the unemployment rate.

The intuition behind this argument is that when vacancies per searcher is high, competition for workers induces firms to raise offered wages to remain competitive. At the same time, workers will have more opportunities to change jobs, leading to a higher quits rate. As a result, the quits rate and vacancies per searcher are key components of the wage Phillips curve and more empirically informative than the unemployment rate or other measures of slack.

Our recent Staff Report confirms this prediction in U.S. data. Crucially, we define searchers as a weighted sum of the number of short-term and long-term unemployed, employed, and non-employed workers, where the weights are based on estimates of these different workers’ search intensities. We then show that quits and vacancies per searcher outperform other standard measures of labor market tightness as predictors of wage growth. The table below demonstrates this point by reporting results from simple univariate regressions of the U.S. wage Phillips curve, ranking indicators by their ability to fit U.S. wage data since 1990. We regress three-month wage growth from the Employment Cost Index (ECI) on the measure listed, where we standardize each of the measures to have mean zero and standard deviation of one to help make comparisons of estimated coefficients. Column “Coefficient” presents the estimated coefficients and column “Fit” shows the regression fit.

We also create a composite measure of labor market tightness that takes a weighted average of quits and vacancies per searcher, using regression coefficients from a regression of wage growth on these two variables as the weights. This composite index, which we call the HPW Tightness Index, is ranked first in the table, indicating that it outperforms all other individual variables. According to the “Fit” column, it explains about 60 percent of wage growth during our sample period. The regression coefficient indicates that a one standard deviation increase in the index is associated with a 0.21 percentage point rise in wage growth.

Quits and Vacancies per Searcher Outperform Other Measures of Labor Market Tightness

| Measure | Coefficient | Fit |

| HPW Index (Quits + V/S) | 0.21 | 0.60 |

| Quits rate | 0.20 | 0.55 |

| V/S | 0.20 | 0.52 |

| Worker gap | 0.18 | 0.44 |

| V/U | 0.17 | 0.41 |

| NFIB difficulty hiring | 0.17 | 0.41 |

| Conf. Board job difficulty | 0.17 | 0.40 |

| Hires/vacancies | 0.17 | 0.38 |

| Unemployment rate | 0.16 | 0.34 |

| Job finding rate | 0.15 | 0.33 |

| Acceptance ratio (AC) | 0.16 | 0.30 |

| Log continuing claims | 0.13 | 0.22 |

| Hires rate | 0.12 | 0.21 |

| Separation rate | 0.00 | 0.00 |

Notes: The “Coefficient” column reports the increase in wages (in percentage points) associated with a one-standard deviation increase in each indicator, while the “Fit” column reports the R‑squared value from simple time-series regressions. All measures of tightness are ordered by their fit. Estimates use data from 1990:Q2–2024:Q2, when quits data are available, or shorter horizons in the few cases where less data are available. We compare quits and vacancies per searcher against the following other measures of labor market tightness: the workers gap (Vacancies-Unemployment)/Labor force; vacancies divided by the unemployment rate; the NFIB survey measure of small businesses’ perception of worker availability; the Conference Board’s survey measure of consumers’ perception of job availability; the hires/vacancies ratio; the unemployment rate; the job-finding rate; the Acceptance Ratio of job-to-job transitions divided by unemployment-to-employment transitions (Moscarini and Postel-Vinay, 2023); the log of the number of continuing claims for unemployment insurance; the hires rate; and the separation rate. Wages are measured using the employment cost index. See Heise, Pearce and Weber (2024) for details.

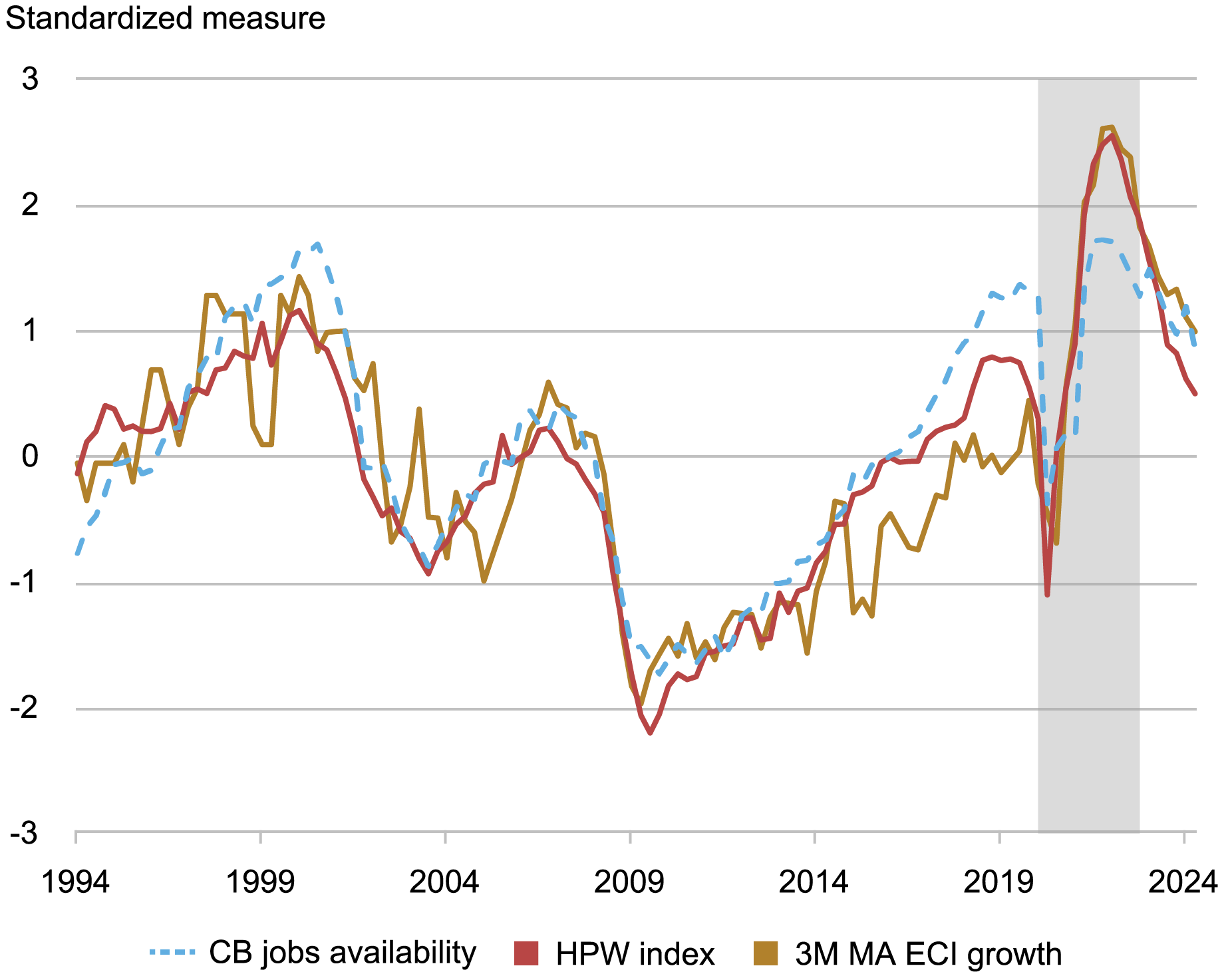

The chart below demonstrates the fit of the HPW Index visually by plotting it against wage growth, measured using a three-period moving average of the three-month growth in the ECI (both series are normalized to have a mean of zero and variance of one for ease of comparison). We compare our measure against a common measure of labor market tightness: the Conference Board’s survey measure of consumers’ perception of job availability. Both the Conference Board measure and the HPW Index track wage growth well in the pre-pandemic period. However, in the pandemic period, our measure performs significantly better.

The HPW Index Tracks Wage Growth Well Even During COVID

Source: Authors’ calculations. Notes: The HPW Tightness Index, based on quits and vacancies per searcher, tracks wage growth well even during the COVID pandemic and recovery. All series are normalized to have zero mean and variance of one for ease of comparison. Wage growth is measured using the employment cost index. “CB Jobs Availability” is taken from the Conference Board. COVID period and recovery 2020:Q1—2022:Q4 is shaded.

No Evidence for Nonlinearities in Wage Inflation

Given recent interest in nonlinear effects of labor market tightness on price inflation (Benigno and Eggertsson, 2024), we also investigate whether there is a nonlinear relationship between labor market tightness and wage inflation. We do not find any evidence of nonlinearities. Indeed, there is nothing unusual in the wage/tightness relationship, either during the period of extreme tightness in the aftermath of COVID, or later. This can be seen in the chart below, where we provide a scatterplot of the HPW Tightness Index against wage inflation. We find a near-linear relationship between the two variables.

No Evidence of a Nonlinear Relationship Between Wage Growth and Labor Market Tightness

Notes: The relationship between the HPW Tightness Index and nominal wage growth appears linear. Wages are measured using the employment cost index. Line fit is a polynomial fit based on local observations.

Concluding Remarks

In summary, the HPW Tightness Index of quits and vacancies per searcher performs well in summarizing labor market tightness for the purposes of determining wage inflation, consistent with theoretical results in Bloesch, Lee and Weber (2024). The relationship remained strong during the COVID period and recovery, suggesting that the empirical relationship documented is robust to even large, unusual economic shocks.

Sebastian Heise is a research economist in Labor and Product Market Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Jeremy Pearce is a research economist in Labor and Product Market Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Jacob P. Weber is a research economist in Macroeconomic and Monetary Studies in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

How to cite this post:

Sebastian Heise, Jeremy Pearce, and Jacob P. Weber, “A New Indicator of Labor Market Tightness for Predicting Wage Inflation,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 9, 2024, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2024/10/a-new-indicator-of-labor-market-tightness-for-predicting-wage-inflation/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

Source link