Every state in the country has a law permitting involuntary hospitalization if a person presents a danger to themselves or others as a result of mental illness. If a person reaches this high bar, the logic goes, they should be confined in a psychiatric hospital for treatment until they are stabilized. (The process is also sometimes called involuntary commitment, involuntary psychiatric hold, or sectioning.) Although there is no definitive national accounting, it is estimated that about 1.2 million involuntary psychiatric hospitalizations occur every year (Lee and Cohen 2021). This puts the magnitude on par with the 1.2 million individuals imprisoned in state, federal, and military prisons every year (Carson 2022). In a new Staff Report, we use data from Allegheny County, which includes Pittsburgh, to measure how psychiatric commitments are impacting an individual’s risk of danger to themselves or others, earnings, and housing.

In the abstract, the impact of an involuntary hospitalization is unclear. During episodes of mental health crisis, involuntary hospitalization may help remove an individual from a dangerous setting and give them access to stabilizing care. This care can in part connect a person to treatment and/or services outside the hospital. Incapacitation may also reduce risk, since individuals are held in inpatient care under supervision and the majority of both violent offenses and suicides are premeditated very briefly (Brouwers Appelo and Oei 2010; Deisenhammer et al. 2009).

On the other hand, involuntary hospitalization may disrupt beneficial social supports such as therapeutic relationships, housing, and employment. Moreover, if individuals find involuntary hospitalization unwelcome, it may degrade trust in the healthcare system, making it harder to access treatment thereafter.

Variance in Physician Behavior

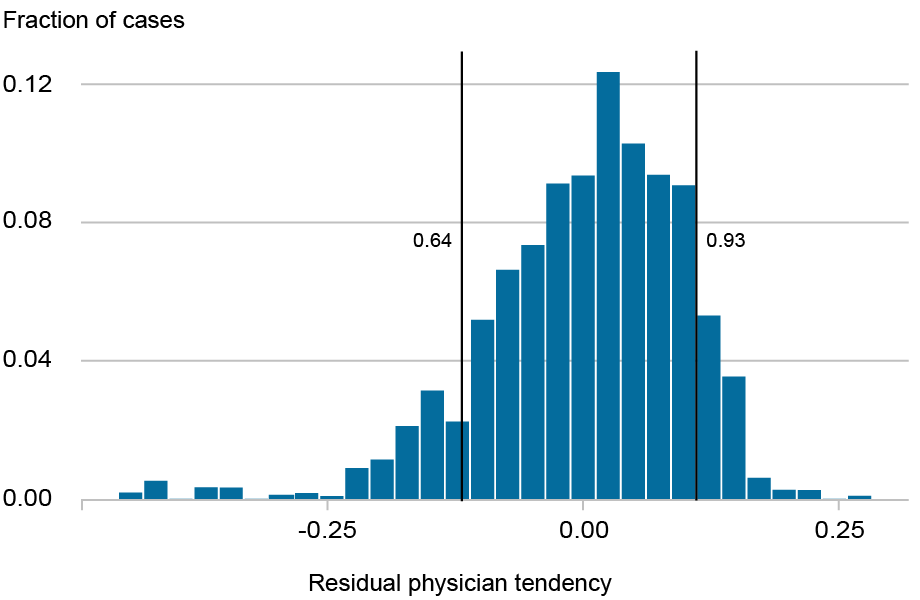

For involuntary hospitalization to proceed, a physician needs to determine that the individual poses a danger to themselves or to others. This evaluation is performed by a physician on staff in the emergency department. We find that once a person has been brought to a given hospital, in a given shift, which physician performs the evaluation is as good as random. This is because there is a very short window in which the evaluation must occur and so the next available physician takes the case. Which physician evaluates a given case is important because physicians vary substantially in what share of cases they refer for involuntary hospitalization. The chart below shows the distribution of physicians’ tendency to involuntarily hospitalize the patients they evaluate. The vertical lines show the 5th and 95th percentile, revealing that physicians at the lower end of the distribution hospitalize as few as 64 percent of the patients they evaluate while those at the upper end of the distribution hospitalize as many as 93 percent.

Distribution of Physicians’ Tendencies to Involuntarily Hospitalize

We leverage this quasi-random assignment to which physician performs the examination in instrumental variables analysis akin to an examiner research design. In a randomized experiment, a patient is randomly assigned to a treatment or control group. In our context, a patient is quasi-randomly assigned a physician for an exam, and that physician may have a high or low tendency to hospitalize patients. We use this variation in examiner behavior to untangle causal effects. By comparing the outcomes among individuals seen by physicians who hospitalize relatively more of their patients to the outcomes among individuals evaluated by physicians who hospitalize fewer of their patients, we can assess the impact of involuntary hospitalization.

The group that could end up in either treatment or control, depending on which physician assesses them, are called the “compliers”—individuals who are, from the perspective of the evaluating physicians, a judgment call for an involuntary hospitalization. We estimate that roughly 43 percent of those evaluated for involuntary hospitalization fall into this group. The result of any instrumental variables analysis only applies to this “complier” group, the judgment call cases.

Danger to Self and Others

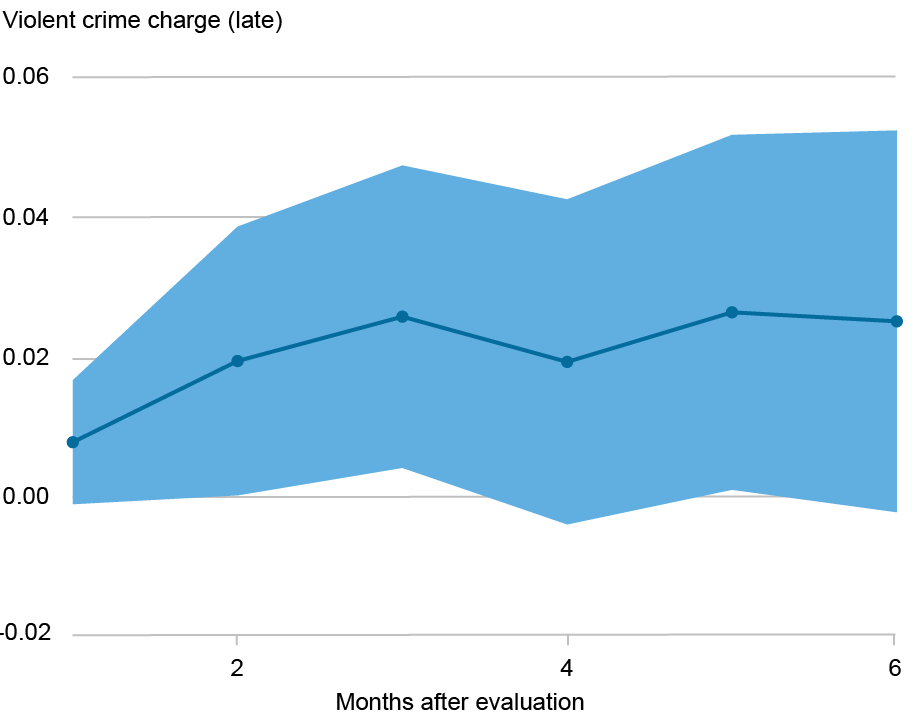

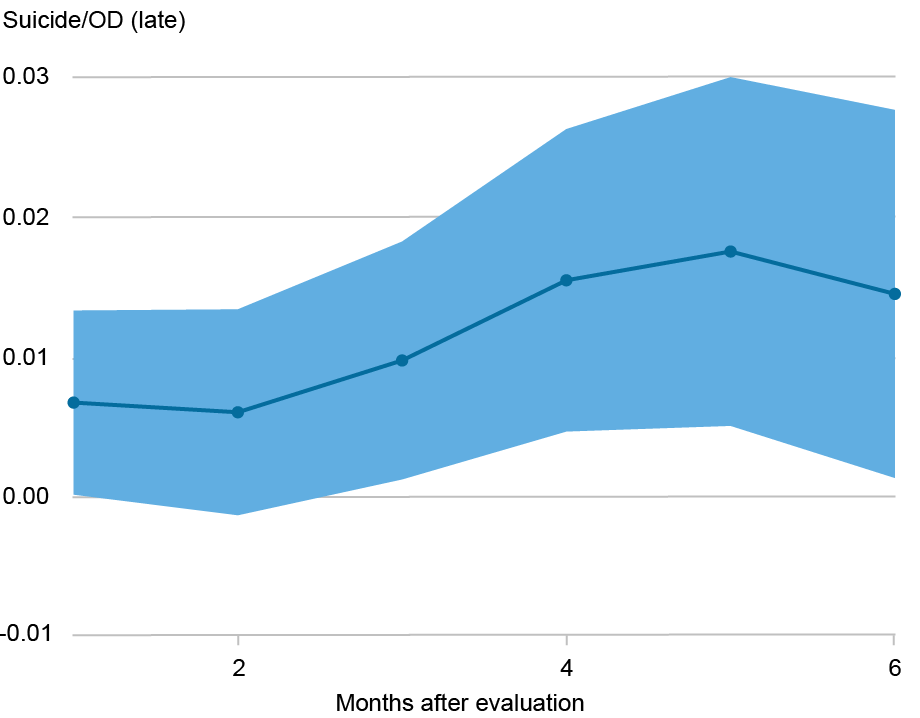

The chart below shows the local average treatment effect (LATE) of hospitalization on being charged with a violent crime or dying by suicide or overdose in the six months following an evaluation.

We find that in these judgment call cases, involuntary hospitalization significantly increases the likelihood of harm to self or harm to others. In particular, for judgment call cases we find that the risk of a being charged with a violent crime in the three months following an evaluation is increased by 2.6 percentage points above a baseline of 3.3 percent (though the chart shows results for each month through the six months after evaluation). Likewise, for judgment call cases, involuntary hospitalization increases risk of dying from suicide or drug overdose death is increased by 1.0 percentage point above a baseline risk of 1.1 percent over a three-month period after evaluation for hospitalization.

Increases in Charges for Violent Crime and Death by Suicide/Overdose for Judgment Call Cases

This result is surprising. Involuntary hospitalizations are a public safety measure, and the finding that they are driving more of the outcomes they seek to prevent in the judgment call subpopulation we study has important policy implications. The significance is especially pronounced since many areas across the country are seeking to scale up involuntary hospitalizations.

Interpretation

Why might involuntary psychiatric hospitalization make someone more likely to die by suicide or drug overdose or be charged with a violent crime? To better understand our main results, we assess whether involuntary hospitalization affects an individual’s earnings and housing status. Using the same instrumental variables approach, we see that earnings drop significantly for those in the “complier” (judgment call) group who are hospitalized. We also see significantly more homeless shelter usage for people who have not used shelter before and are among these judgment call cases, indicating a destabilization of housing.

We do not observe significant improvements in medication adherence or engagement with outpatient care in the months after the judgment call evaluations, indicating that involuntary commitment is not significantly connecting judgment call individuals to care.

This evidence together suggests that, on net, the destabilizing forces are more powerful than the therapeutic ones for the “complier” (judgment call) group we assess in this study. This connects with prior evidence that destabilizing forces can increase the likelihood of adverse outcomes (Lin 2008; Sullivan and von Wachter 2009; Eliason and Storrie 2009; Dobkin et al. 2018). It also connects to related research documenting that defensive medicine can have adverse consequences for patients’ wellbeing (Kessler and McClellan 1996; Studdert et al. 2005).

The result has broad policy implications. Public cases in which persons who have not been involuntarily hospitalized and have subsequently engaged in violent behavior have prompted calls for expansions of involuntary hospitalization (Hirschauer 2025). Our results suggest that, if involuntary hospitalization systems in other areas have similar effects on patients to those we document in our study, it may be worth exploring additional or alternative measures to support individuals in mental health crises.

Moreover, our analysis suggests multiple lines of future research. Outcomes among those evaluated for involuntary hospitalization are very poor, whether they are hospitalized or not (Welle et al. 2023), suggesting a need to develop better forms of care for people facing psychiatric emergencies. The more we understand when involuntary hospitalization is likely to improve patient outcomes and when it is likely to hurt outcomes, the better targeted this intervention can be.

Lastly, from a fairness lens more work should be done to assist physicians in their decision-making processes and to reduce the variance across physicians in the tendency to hospitalize. Better utilization of scarce healthcare resources, including emergency and inpatient hospital beds, has the potential to improve care for all.

Natalia Emanuel is a research economist in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

Pim Welle is chief data scientist for the Allegheny County Department of Human Services in Pittsburgh, PA.

Valentin Bolotnyy is a Kleinheinz Fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution.

How to cite this post:

Natalia Emanuel, Pim Welle, and Valentin Bolotnyy, “A Danger to Self and Others: Consequences of Involuntary Hospitalization,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, October 15, 2025, https://doi.org/10.59576/lse.20251015

BibTeX: View |

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the author(s).

Source link